Tehuelche was the name given by the Mapuche to the people inhabiting the Pampa on the northern coast of the Strait of Magellan. European sailors called them “Patagones” (“bigfoot”), giving the territory its name and endowing the land with the aura of a mythical land inhabited by giants.

Although the Tehuelche had a common way of life and language, different dialects and local particularities were apparent among the different subgroups. These included the “Aonikenk” people who inhabited the Magallanes region, groups living inland in the Aysen region, and others that had settled near the Argentinean border on the mainland adjacent to Chiloe Island, and who had only indirect contact with the other Telhuelche groups.

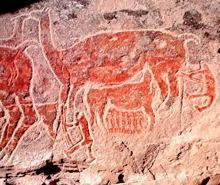

he origins of the Tehuelche can be traced back 4500 years in archeological sites that display very similar technology, diet and housing patterns. Two distinct stages of Tehuelche cultural development can be distinguished. The first is the pedestrian stage, documented in the writings of early European travelers. During that stage the Tehuelche numbered around 4,000–5000, divided into nomadic groups of up to 100 members each. These groups lived by hunting guanaco and the ostrich-like ñandú and collecting food along the coast. They used bows and arrows as well as bolas for hunting.

During the second stage, the Tehuelche’s adoption of the horse revolutionized their way of life. The wild horses they captured were the descendants of animals that had escaped from or been abandoned by colonists in the 16th Century. Finding the environment favorable, the horses had reproduced and spread throughout Patagonia. Using horses allowed the Tehuelche groups to increase their range significantly, and therefore their size. Groups swelled to 400–800 riders each, bringing them into contact with neighboring groups more frequently and under more varied circumstances. Despite the harsh climate, the increased contact tended to homogenize the native way of life across Patagonia, with the Mapuche exerting a strong influence in the 18th and 19th centuries.

In 1876 the first sheep were brought to Patagonia, and their favorable adaptation launched the colonization of the area. In 1878, the Argentine government began to grant concessions regularly to colonists, and by 1884-1885 ranches were being established in the interior, in the southern part of Tehuelche territory. As large tracts of land were fenced off for sheep ranching, the natives began to lose their traditional access to natural resources.

Between 1876 and 1893, the indigenous people saw most of their territory occupied by colonists, as the traditional hunting grounds also happened to be the best pastureland. This forced the Tehuelche groups to break into smaller units and adapt to this new configuration. By early 1890 there were some half-dozen autonomous groups, each with around 300-400 members. These groups amalgamated over time into larger units, and by 1893 there were just three Tehuelche communities. Two of these were forced to abandon their traditional nomadic way of life as the guanaco population was reduced by the steady expansion of sheep ranching. Despite this infringement, however, the Tehuelche communities did manage to establish peaceful trade relations with the colonists, choosing to breed and trade horses, raise sheep and cattle, or take paid employment in nearby ranches. This accelerated their assimilation into western society’s mode of production and, despite some concern shown by local authorities, the Tehuelche were decimated by their exposure to new diseases and alcohol and by their exclusion from their traditional lands, for which they could not obtain legal title as they were not deemed to be citizens with rights.

The last surviving Tehuelches lived on the reserves of Camusu Aike and Lago Cardiel, in what is today Argentina. A number of nearby communities still claim Tehuelche heritage there today.