Textile making is one of the most important technologies ever developed by humans. Textiles perform a variety of utilitarian functions: Among many others, they protect people from the elements and allow them to carry things (in woven bags, for example). Since ancient times, however, textiles also have been used as a medium to transmit ideas about customs, social organization and religion, making them a powerful cultural instrument for representing the ideology of a given group of people.

Textiles are structures composed of one or more systems of interlaced elements or threads. Traditionally they were made from animal and/or plant fibers, more recently from man-made fibers as well. Textiles can be classified into two main groups, depending on the thread system: The first category includes those made with a single system of threads interlaced in one direction, either horizontally or vertically. The threads can be worked loose or attached to a stretcher. Twisted, braided, looped and knotted textiles fall into this category. Textiles in the second category have a horizontal thread system (weft) interwoven with a vertical one (warp) using a device known as a loom.

Textiles produced with a single thread system were developed long before those involving two systems. In ancient times, needles or other tools were used to knot or interlace fibers to produce hunting and fishing implements such as nets. The manufacturing of yarn or thread was a decisive advance in textile making, allowing fine, weak and/or short animal hair or plant fibers to be transformed into longer, stronger fibers by twisting or spinning them together using simple implements such as spindles and counterweights.

The earliest evidence of textiles, dated at 15,000 BCE, was found in the Lascaux caves of France and consists of a fragment of plant fiber cord with three threads twisted together. Representations of similar fiber cords appear some 5000 years earlier, however, associated with the so-called “Paleolithic Venuses”. These figures are depicted with skirts or aprons made of twisted cord bound together. Although the material used to make these textiles is not known, they are thought to have been made of animal tendons or some kind of plant fiber.

When no material evidence has been preserved, the existence of a textile industry is inferred through discoveries of related artifacts such as needles, counterweights and spindles, or through visual representations such as ceramic art, stone sculpture, rock art and temple wall murals. The earliest examples of this kind of evidence include textile impressions left on ceramic figurines and vessels from the ancient Jomon ceramics of Japan and the earliest American ceramic traditions that emerged in Ecuador 6,000 years ago. In Europe, however, textile instruments such as needles have been found at Upper Paleolithic sites dated between 19,000 and 15,000 BCE. In the Middle East, the tombs at Çatalhöyük dated at 6000 BCE include bodies wrapped in woven blankets. The first crops of flax, a plant whose fibers are used to make thread for textile making, are dated at 8000 BCE. Egyptian textiles were also made using this plant, and multiple discoveries have been dated at around 5500 BCE. Evidence of Chinese silk making, one of the world’s most famous and ancient textile industries, has been dated as early as 5000 to 3000 BCE. This industry was based on the domestication of the silk worm by the Yangshao people who lived on the banks of Yellow River in northwest China.

In the Americas, especially in the Andean region, textile making was an important and highly developed technology that produced some of the most sophisticated textile traditions in the world. The arid conditions of the Andean coast and the Altiplano have enabled the preservation of much of this fragile artistic legacy; in some areas textile fragments have been discovered that date back 8000 years. Textiles were important to pre-Colombian Andean cultures as medium for representing identity, social hierarchies and civil status, as an instrument of tribute and a symbol of social prestige. This is demonstrated in the oldest known textile finds in this area, which come from the coastal archaeological site of Huaca Prieta, located in the Chicama Valley of northern Peru. The textiles found there, dated at 3000 to 2200 BCE, display animal figures such as felines, serpents and condors, as well as anthropomorphic and other unidentified figures made with yarn of different naturally and artificially dyed colors. Images 3, 4

These are the earliest examples of Andean textile iconography, a tradition that would continue for the next 4000 years, making woven textiles the medium of choice for artistic and religious expression in the region. The textiles referred to were made of plant fibers and cotton, which has been grown since ancient times on the Peruvian coast. It was not until much later that groups began to make textiles from the hair of the camelids that inhabited the highlands of this region. Its use was limited on the coast, however, indicating that camelid hair yarn was a scarce and probably highly valued commodity.

These ancient Andean textiles were made using a special instrument, called a loom, to separate the vertical threads (warp) and then interlace them with horizontal ones, called the weft. This interlacing produced a woven textile structure, the most elementary form of which is called “plain weave”. Image 2 Around 1400 BCE, the development of heddle weaving allowed several warp thread systems to be used simultaneously, an important technological advance that streamlined the weaving process enormously and spurred the growth of the textile industry in the Andes. By around 2000 BCE in places such as La Galgada, in the sierra of northern Peru, textile making had developed to include much wider cloth with multiple thread systems, while decorative elements were often reduced to vertical stripes in different colors. The fact that textile makers of this period favored the production of broad woven pieces in plain weave points to the existence of a quicker, more efficient weaving process.

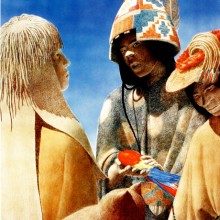

Later on, the region developed a flourishing industry with groups such as the Paracas culture becoming one of the most prolific textile-making cultures in the Americas. Vestiges of this group’s legacy have been found in several valleys in southern Peru including Pisco, Ica and Nazca. During this period a huge variety of decorative and weaving techniques were developed, the most notable of which was embroidery, which allowed textile artists to produce curved lines to represent figures not only in frontal and profile views but in action positions. These images became more complex over time, foreshadowing the eventual development of the Nazca culture (100 BCE–700 CE) image 14, whose textile tradition displays virtually the entire repertory of techniques and colors available in the Andes at the time. Indeed, many techniques that were common then would disappear as the Nasca culture declined. The techniques developed were used to create fine embroidered textiles with volumetric finishings, representations of anthropomorphic figures and lifelike, multicolored, and curved motifs that would later take on more geometric forms, which were repeated on the cloth to make patterns image 1, 13. The Nazcas also made a variety of accessories for daily use, including sashes, bags, sandals, fans, hats, turban headdresses and headbands, using the same techniques, images 15,16,17.

Later textile traditions continued to use these techniques and styles, although in the case of the Wari and Inka cultures images 6, 7, tapestry weaving was the preferred mode. Another notable post-Nazca textile industry is that of the Chancay people (1000 to 1430 CE), who lived on the central coast of Peru and produced an unequalled repertoire of fine gauzes, reticulated weaves, brocades and openwork tapestries, as well as funeral masks and 3-dimensional dolls images 8,9,10 . The textiles of the northern Peruvian Chimú culture (900 to 1,400 C.E.) are also worth noting. These featured multi-item ceremonial and funerary outfits made with feather, metallic and volumetric woven appliqués. Images 11,12

In the Inka Empire textiles were used not only as clothing, decoration and a medium for representing images, but also to keep records and tell stories. The Inka quipu –which means ‘knot’ in the Quechua language– was an implement made from cords that were knotted in different ways to record census and tax information. Spanish historians affirm that they were also used to relate stories, genealogies, poems and songs. Researchers have deciphered some of the ways in which the quipus were used to record quantitative information, but how they were used to record myths and other stories remains a mystery.

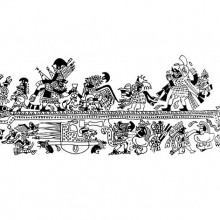

In Meso-America, the development of the pre-Colombian textile industry has been studied primarily through images and representations in other media such as ceramics, stone sculptures and painted murals. Further information has been obtained from descriptions left by the conquistadors and from present-day indigenous traditions. Unfortunately, the prevailing climatic conditions in some regions of Meso-America, especially the high humidity, caused these fragile materials to decompose. However, some direct archeological evidence has been found in caves located in the present-day states of Puebla and Tamaulipas, in south-central and northern Mexico, respectively. These finds include fragments of cords and nets dated between 5000 and 2500 BCE, indicating that this craft developed early in the region. The first loom-woven textiles appear much later, as small items that were usually made on a belt-loom. The more decoratively and technically complex of these early artifacts are assumed to have been worn by leaders, while the simpler items are thought to have been used by ordinary people. These ancient textile artifacts were made primarily of plant fibers, with occasional decorative elements such as feathers or animal hair. Cotton, which had been cultivated since earlier times, was normally reserved for the clothing of the elite class, such as woven capes (tilmas) and armor, while the loincloths, underskirts (enredos) and tunics (huipiles) used by ordinary people were made from the harder plant fiber. Together these made up the basic attire of the Mesoamerican people, with some regional and cultural variations identified from 1200 BCE up to the arrival of the Spanish. Some elements of this traditional textile-making industry even have survived to this day.

The oldest evidence of weaving in Meso-America was an imprint on ceramic found in the Valley of Tehuacán and dated at 1500 to 900 BCE. But the only direct evidence of loom-woven textiles that has been preserved is dated at 200 to 300 CE and corresponds to two cloth items that were used to wrap a mummified body found in a cave at Coxcatlán, in the same Valley of Tehuacán. These items are of simple manufacture but are decorated with bands of different colors.