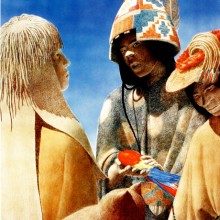

Colonial writers and later travelers have left little information relating to Chango arts and handicrafts, providing only a few details of the tribe’s daily life and the materials they used. These refer mainly to their boats and their tents, which were of a design known as the ruca. The Changos seem to have dressed in simple attire made from alpaca or vicuña wool and sea lion skin, and they anointed their hair with sea lion grease. This made their heads shine in the sun, contrasting with their dark skin.

Their tools, utensils and dwellings were simply but skillfully made and were specially suited to their nomadic, seafaring way of life. The Chango culture adopted raw materials, technologies and objects from distant cultures, adapting them to their particular needs; examples of this include pottery, metallurgy and textile making techniques.

Archaeological studies of Chango cemeteries and dwelling places dating from the era of the Spanish conquest have shed new light on the culture’s handicrafts. Clothing items recovered include camelid (llama, alpaca and vicuña) wool caps, pelican feather headdresses, sea lion skin coverings, wool blankets and sea bird pelts. The oldest sites have also yielded leather loincloths with cords made from plant fibers and camelid wool.

Many cotton and wool clothing items found show signs of having been patched or repaired on many occasions, or reused for other purposes. This suggests that such goods were hard to come by, and many were likely obtained through barter with inland groups.

Along with their clothing, the Changos wore bracelets and necklaces made from seashell pieces, stones, bone, and even sea lion teeth. They also used seashells to make spoons and knives. Their ceramic vessels were for domestic use, simple in design but varied in shape. Such goods were probably also obtained through trade, rather than being manufactured by the Changos themselves.

They used copper to make fishing hooks and ornaments such as earrings, bracelets and pins. Wood was a highly-prized commodity on the coast, and the wooden items found at Chango sites–such as boxes and boards–were probably also obtained from other tribes.

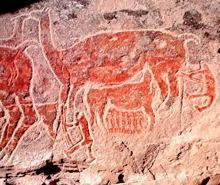

Without a doubt, however, rock paintings are the most noteworthy art the coastal peoples produced. Well-known examples include those found at the El Médano site, located in a ravine to the north of Taltal. There, for about 10km (about 6 miles), the rocks and crags that line the creek’s course are covered in rock art paintings depicting scenes from the daily life of these fishermen of a thousand years ago, drawn in red pigment. The pictures show people hunting and harpooning from sea lion skin rafts, as well as catching fish, turtles, sea lions and whales. Other images depict dogs or foxes, and camelids.

Other sites in the same region (such as Las Lizas beach south of Chañaral) have similar paintings, in addition to engravings of sea lions, dolphins and whales, and hunting scenes involving land animals. These works are rich in symbolic meaning, and could have been intended to safeguard the group’s survival and reproduce its social structure, as well as protect it from shortages of food.