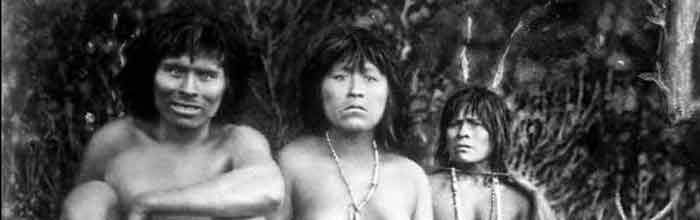

According to the German Catholic priest Martin Gusinde, the Yaghan believed in a supreme being called Watawineiwa, the owner of all that exists, the one who gives life and takes it away, and the provider of all plants and animals. The tribe’s moral code represents his will, and the Yaghan prayed to him freely with thanks and requests for protection. Their belief system can be classified as animist, with all natural phenomena ‘culturalized’ as spirits. The tribe’s cosmic vision was a solemn topic, and therefore conversations on this topic were rare.

In contrast, the discussion of moral issues and principles was an everyday affair, with the people taking a simple approach even for matters of a profound nature. Rituals were practiced in an irregular, more personal manner.

Yekamus or shamans were very powerful in Yaghan society. They were respected and feared but not trusted, and the community had no power over them. They trained as apprentices individually with older shamans or in ‘shaman schools’—loima-yekamus. There the apprentices learned healing, prediction, how to assist the hunt. There were no special requirements for performing this ceremony. Yekamu candidates were young men who demonstrated the skill and disposition for this role and they chose their vocation freely. Candidates were made to withstand rigid positions, sleep and food deprivation and long periods of silence to enhance their sensitivity and nervous temper, which would help them access the dream world. In becoming a yekamu, an apprentice had to give up his own personality and be taken over by a spirit.

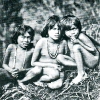

The Ciexaus was an important element in Yaghan spiritual practice. Boys and girls both underwent this rite of passage at puberty, and its aim was to prepare the aspirants for adult life through physical trials. After undergoing this rite, individuals became full members of the Yaghan community. The ceremony was imbued with the tribe’s rich spiritual heritage.

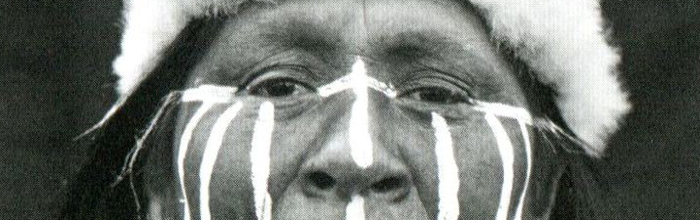

The Kina ceremony came later in life and was restricted to young men, introducing them to the mythological ideas that Yaghan men considered their sole preserve. However, there were no negative consequences if a man failed to participate in this ritual, and years could go by without the ritual being performed. The main aim of the Kina seems to be to remind women of the men’s supremacy. Indeed, the rite appears out of place in the Yaghan social order, and seems to have been adopted from the neighboring Sek’nam people. The last ceremonies of this kind recorded took place between 1920 and 1923.

There was also a mourning ritual, consisting of a mock battle between men and women, in which the whole group participated. The body and possessions of the deceased were then cremated in a location that was avoided for many years afterwards, and the name of the deceased was never again mentioned. The Yaghan people—and their shamans especially— had a great fear of the dead.

Other Yaghan funeral practices included wrapping the body in animal skins and tree bark and leaving it in a rocky shelter. The burial of the dead in middens or underground are customs that seem to have been introduced by missionaries. According to the German Catholic priest Martin Gusinde, the Yaghan believed in a supreme being called Watawineiwa, the owner of all that exists, the one who gives life and takes it away, and the provider of all plants and animals. The tribe’s moral code represents his will, and the Yaghan prayed to him freely with thanks and requests for protection. Their belief system can be classified as animist, with all natural phenomena ‘culturalized’ as spirits. The tribe’s cosmic vision was a solemn topic, and therefore conversations on this topic were rare.

In contrast, the discussion of moral issues and principles was an everyday affair, with the people taking a simple approach even for matters of a profound nature. Rituals were practiced in an irregular, more personal manner.

Yekamus or shamans were very powerful in Yaghan society. They were respected and feared but not trusted, and the community had no power over them. They trained as apprentices individually with older shamans or in ‘shaman schools’—loima-yekamus. There the apprentices learned healing, prediction, how to assist the hunt. There were no special requirements for performing this ceremony. Yekamu candidates were young men who demonstrated the skill and disposition for this role and they chose their vocation freely. Candidates were made to withstand rigid positions, sleep and food deprivation and long periods of silence to enhance their sensitivity and nervous temper, which would help them access the dream world. In becoming a yekamu, an apprentice had to give up his own personality and be taken over by a spirit.

The Ciexaus was an important element in Yaghan spiritual practice. Boys and girls both underwent this rite of passage at puberty, and its aim was to prepare the aspirants for adult life through physical trials. After undergoing this rite, individuals became full members of the Yaghan community. The ceremony was imbued with the tribe’s rich spiritual heritage.

The Kina ceremony came later in life and was restricted to young men, introducing them to the mythological ideas that Yaghan men considered their sole preserve. However, there were no negative consequences if a man failed to participate in this ritual, and years could go by without the ritual being performed. The main aim of the Kina seems to be to remind women of the men’s supremacy. Indeed, the rite appears out of place in the Yaghan social order, and seems to have been adopted from the neighboring Sek’nam people. The last ceremonies of this kind recorded took place between 1920 and 1923.

There was also a mourning ritual, consisting of a mock battle between men and women, in which the whole group participated. The body and possessions of the deceased were then cremated in a location that was avoided for many years afterwards, and the name of the deceased was never again mentioned. The Yaghan people—and their shamans especially— had a great fear of the dead.

Other Yaghan funeral practices included wrapping the body in animal skins and tree bark and leaving it in a rocky shelter. The burial of the dead in middens or underground are customs that seem to have been introduced by missionaries. According to the German Catholic priest Martin Gusinde, the Yaghan believed in a supreme being called Watawineiwa, the owner of all that exists, the one who gives life and takes it away, and the provider of all plants and animals. The tribe’s moral code represents his will, and the Yaghan prayed to him freely with thanks and requests for protection. Their belief system can be classified as animist, with all natural phenomena ‘culturalized’ as spirits. The tribe’s cosmic vision was a solemn topic, and therefore conversations on this topic were rare.

In contrast, the discussion of moral issues and principles was an everyday affair, with the people taking a simple approach even for matters of a profound nature. Rituals were practiced in an irregular, more personal manner.

Yekamus or shamans were very powerful in Yaghan society. They were respected and feared but not trusted, and the community had no power over them. They trained as apprentices individually with older shamans or in ‘shaman schools’—loima-yekamus. There the apprentices learned healing, prediction, how to assist the hunt. There were no special requirements for performing this ceremony. Yekamu candidates were young men who demonstrated the skill and disposition for this role and they chose their vocation freely. Candidates were made to withstand rigid positions, sleep and food deprivation and long periods of silence to enhance their sensitivity and nervous temper, which would help them access the dream world. In becoming a yekamu, an apprentice had to give up his own personality and be taken over by a spirit.

The Ciexaus was an important element in Yaghan spiritual practice. Boys and girls both underwent this rite of passage at puberty, and its aim was to prepare the aspirants for adult life through physical trials. After undergoing this rite, individuals became full members of the Yaghan community. The ceremony was imbued with the tribe’s rich spiritual heritage.

The Kina ceremony came later in life and was restricted to young men, introducing them to the mythological ideas that Yaghan men considered their sole preserve. However, there were no negative consequences if a man failed to participate in this ritual, and years could go by without the ritual being performed. The main aim of the Kina seems to be to remind women of the men’s supremacy. Indeed, the rite appears out of place in the Yaghan social order, and seems to have been adopted from the neighboring Sek’nam people. The last ceremonies of this kind recorded took place between 1920 and 1923.

There was also a mourning ritual, consisting of a mock battle between men and women, in which the whole group participated. The body and possessions of the deceased were then cremated in a location that was avoided for many years afterwards, and the name of the deceased was never again mentioned. The Yaghan people—and their shamans especially— had a great fear of the dead.

Other Yaghan funeral practices included wrapping the body in animal skins and tree bark and leaving it in a rocky shelter. The burial of the dead in middens or underground are customs that seem to have been introduced by missionaries. According to the German Catholic priest Martin Gusinde, the Yaghan believed in a supreme being called Watawineiwa, the owner of all that exists, the one who gives life and takes it away, and the provider of all plants and animals. The tribe’s moral code represents his will, and the Yaghan prayed to him freely with thanks and requests for protection. Their belief system can be classified as animist, with all natural phenomena ‘culturalized’ as spirits. The tribe’s cosmic vision was a solemn topic, and therefore conversations on this topic were rare.

In contrast, the discussion of moral issues and principles was an everyday affair, with the people taking a simple approach even for matters of a profound nature. Rituals were practiced in an irregular, more personal manner.

Yekamus or shamans were very powerful in Yaghan society. They were respected and feared but not trusted, and the community had no power over them. They trained as apprentices individually with older shamans or in ‘shaman schools’—loima-yekamus. There the apprentices learned healing, prediction, how to assist the hunt. There were no special requirements for performing this ceremony. Yekamu candidates were young men who demonstrated the skill and disposition for this role and they chose their vocation freely. Candidates were made to withstand rigid positions, sleep and food deprivation and long periods of silence to enhance their sensitivity and nervous temper, which would help them access the dream world. In becoming a yekamu, an apprentice had to give up his own personality and be taken over by a spirit.

The Ciexaus was an important element in Yaghan spiritual practice. Boys and girls both underwent this rite of passage at puberty, and its aim was to prepare the aspirants for adult life through physical trials. After undergoing this rite, individuals became full members of the Yaghan community. The ceremony was imbued with the tribe’s rich spiritual heritage.

The Kina ceremony came later in life and was restricted to young men, introducing them to the mythological ideas that Yaghan men considered their sole preserve. However, there were no negative consequences if a man failed to participate in this ritual, and years could go by without the ritual being performed. The main aim of the Kina seems to be to remind women of the men’s supremacy. Indeed, the rite appears out of place in the Yaghan social order, and seems to have been adopted from the neighboring Sek’nam people. The last ceremonies of this kind recorded took place between 1920 and 1923.

There was also a mourning ritual, consisting of a mock battle between men and women, in which the whole group participated. The body and possessions of the deceased were then cremated in a location that was avoided for many years afterwards, and the name of the deceased was never again mentioned. The Yaghan people—and their shamans especially— had a great fear of the dead.

Other Yaghan funeral practices included wrapping the body in animal skins and tree bark and leaving it in a rocky shelter. The burial of the dead in middens or underground are customs that seem to have been introduced by missionaries.