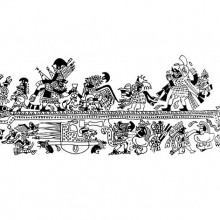

Corn (Zea mays), known as maize in Latin America, was the staple food of the pre-Columbian peoples of the Americas. The Spaniards called it “the people’s grain” and “bread of the Indies”, equating it to Old World wheat and barley. To a greater or lesser degree, this singular species of grass made its presence felt in all spheres of life—social, political, economic and religious—and held a central position in the cosmogony and creation myths of cultures throughout pre-contact Americas.

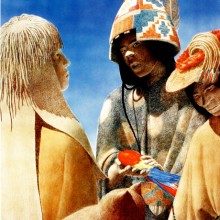

Corn was domesticated more than 8000 years ago, first in the Mexican plateau (Tehuacán) then around 2000 years later in the Andes. At the time of the European conquest, different species of corn were being grown and consumed by farming groups from North America all the way to south-central Chile, as reflected in the many different terms used for this plant: “Maíz” is a Taíno word from the Antilles that is used in Latin America to this day to denominate the corn plant; the Aztecs used the word “elote”, from the Náhuatl word elotl, to refer to the corncob and grains of corn; and in many parts of South America this cereal is called “choclo” or chuqllu, a Quechua word that came into common usage throughout the Andean region during the Inca Empire. Highly versatile, corn was the base ingredient for many staple foods that have remained virtually unchanged since ancient times. Corn flour has been used to make pastries, tortillas, bread, tamales and humitas, and as a common ingredient in stews (combined with beans and/or meat). In the Andes, corn is toasted, dried and ground up to produce chuchoca. Since pre-Hispanic times it has also been fermented to produce slightly alcoholic beverages, called “tepache” by the Aztecs, “chicha” in the Andes, and “muday” by the Mapuche people of south central Chile. These beverages were used in religious ceremonies and ritually consumed by leaders entering into important political agreements.

Along with vanilla, corn was one of the first American products to reach Europe: by the end of the 16th Century it was already being cultivated in Spain, but only as animal feed. Ignorance of its food value for humans delayed its introduction into the Old World diet: when it was eaten alone, without being combined with plant or animal protein as was the custom in the Americas, people suffered severe nutritional ailments. It would take another hundred years before corn became a common food in Europe. After this, it spread to Guinea and Asia Minor, and ultimately Africa, where it helped to alleviate hunger in a region where food was scarce.