Ceramics is one of the most revolutionary technologies in human history, and the first completely synthetic product to be made by humans. It combines three basic elements: the first is clay, the second additives—organic or inorganic elements found in or deliberately mixed with the clay to make it more workable and prevent breakage under extreme heat—and the third is water, which gives the material a malleable consistency. The step from modelling figures with raw clay to the application of fire to make a solid, durable objectwas the main development that gave rise to this technology. Ceramics are among the materials that best withstand the passage of time, and as such are a major source of information for archaeologists as they seek to learn about the past.

Many questions about the origins of ceramics remain unanswered. The earliest known evidence of ceramic technology are the clay figures found in Dolní Vĕstonice, a Gravettian Palaeolithic site in the modern day Czech Republic and dating back around 26,000 years. These figures are a very early example of experimentation with clay; thousands of fragments of both fired and raw clay have been found at the site, as well as evidence of a kiln, confirming the existence of sophisticated knowledge and skills in the use of these items. Most of these figurines are the so-called “Palaeolithic Venuses”, small statues of women with exaggerated breasts and abdomens to accentuate their femaleness. Image 1

The question remains, however, as to when the idea first arose to use clay and other materials to make vessels, a development that would turn a technique into a revolutionary technology. The world’s oldest pottery is the Jōmon tradition, from Japan. The style dates back to between 8000 and 4000 BCE, and is consists of basket-shaped pieces with surfaces showing the imprints of cords and rope coils. Ancient oriental pottery in both China and Japan achieved a high level of sophistication thanks to the emergence of techniques such as glazing and the development of more efficient kilns, which could attain the high temperatures needed to produce porcelain. The introduction of the potter’s wheel, a revolving circular platform on which a lump of clay could be modelled as the base rotates, was another advance in technology that facilitated large-scale production.

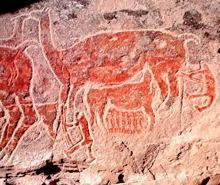

The earliest evidence of ceramic technology in the Old World comes from two sites in the Middle East— Beldibi and Çatalhöyük, both in Southern Turkey—dated at around 6500 B.C.E. These early vessels were hand made from rolls of clay, then rubbed or scraped to attain a more even finish and fired in wood or dung fires. One hypothesis on the birth of ceramic technology in this area links it directly to the development of early architecture in the Middle East, as both ceramic vessels and buildings were made by placing pieces on top of each other to produce the desired form. Image 2

In general, the rise of ceramics has been associated with the development of agriculture and a sedentary way of life. However, there are some cases of nomads and hunter-gatherers using ceramics, including the earliest known ceramics of the Americas. On the banks of the Magdalena River on the Caribbean coast of Colombia, examples of ceramic work have been found dating back to 3490 B.C.E. The San Jacinto 1 site, located in this riverbank area, is thought to have been occupied for long periods by humans groups that subsisted by collecting wild seeds and hunting small game and deer. Ceramics found here consist of small bowls, pitchers, and globular neckless vases with handles. Image 3

Valdivia pottery is another expression of early ceramics in the Americas. Artefacts from this tradition have been found at a number of sites on the Santa Elena peninsula on Ecuador’s Pacific Coast. One of the best-studied sites is Real Alto, where a number of finds have been dated between 3000 and 2300 BCE. In earlier sites, such as nearby Altomayo, ceramic figurines have been found that might represent the experimentation stage preceding the development and adoption of ceramic technology. These figurines have features very similar to experimental ones found in Eastern Europe and the Middle East.

Around a thousand years later, ceramics began to appear in the archaeological record of Mesoamerica and the Andes. Some of these were found around the year 2000 B.C.E. in the Peruvian Amazon’s Ucayali River valley, about the same time the technology emerged in the country’s northern and central coastal regions in association with early agricultural communities and the first examples of monumental architecture.

In the Mesoamerican region, the development of ceramics is best known from the Tehuacán Valley in Southern Mexico. The emergence of agriculture has been studied intensively at the site, and it is believed that the emergence of ceramic technology was closely related with this change in lifestyle, particularly during the Purrón Phase, from around 2300 B.C.E. The shapes of ceramic vessels found there imitate the stone mortars that were used to grind the first cultivated grains. The most popular and widely used ceramic form across the Mesoamerican region, however, was the tecomate, a gourd-shaped bowl used to store seeds.

The most widespread early ceramic tradition in Mesoamerica was that of the Ocós, which developed around 3500 B.C.E. in coastal and riverbank sites and resembled the Valdivia tradition. This similarity has sparked speculation that ceramic technology developed across the region through contact among these groups. Most ceramic items were made for domestic use, but some were also used as grave goods or as ornaments, figurines, and musical instruments, giving ceramic artefacts a religious significance among ancient cultures.

Although the earliest evidence of ceramics in the Americas predates the development of agriculture and a sedentary way of life, this technology certainly was used more intensely in communities that produced their own food and lived in small villages.