Tallado en piedra de una punta de dardo o flecha

Ver animación

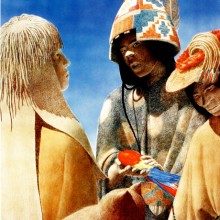

Stone carving or knapping is the oldest human technology in the archaeological record. It began to appear one to two million years ago, when the first humans began using simple stones as hammers and cutting tools, modifying their natural shape by striking them against each other to produce angular, sharp-edged tools. Over time their skills improved and new techniques were developed to work stone into useful items. Image 1

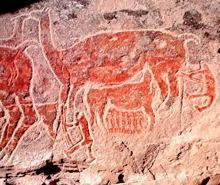

Rocks are found in almost all natural environments, but not all are equally suitable for tool making. The most widely used were crystalline rocks such as quartz, chert, and flint, and volcanic glasses, as striking or pressuring these produced predictable fractures that allowed tools to be shaped. Imagen 2

Once a knapper selected a nodule of suitable rock, he removed the outer layer, which is normally rough from its exposure to the elements. The smooth, regular interior of a single nodule could then be worked into several tools. Knapping is a complex process that requires careful planning, as each blow can be made only once and errors can have a major effect on the finished piece, even rendering it unusable and forcing the knapper to start over again.

Depending on the tool being made, the knapper faced a series of decisions as he worked a core of stone. Some solid objects, such as large hammers, were made by chipping off small flakes of the outer layer of the nodule, giving shape to the inner core. Thin cutting tools such as knives were made by working on chips struck off the core with sharp blows. These thin, sharp slices of rock are known as flakes.

Flakes of flint or similar rock could be used unworked as long as their edges were kept sharp, or could be knapped into more complex pieces such as arrowheads or knives. Modifications made to these flakes included serrated edges and blunt edges, which allowed them to be held in the hand or inserted into a handle. Tools that had lost their cutting edge could also be reworked to make them sharp again.

Knappers would often strike the rock they were working on directly, using a harder pebble. This would guarantee that the piece would break, but an intense blow would reduce the craftsman’s control over the line of fracture, rendering the process unpredictable. By using softer strikers made from wood, bone, or antler, the force of the blow could be reduced and the knapper could exert more control over how the workpiece would break.

When greater precision was required, the knapper used an intermediate tool rather like a chisel, which would transmit the force of the blow through to the workpiece, cushioning the impact or directing it to a specific point. This knapping technique is called soft-hammer percussion.

The way in which the workpiece was held would also affect the result of the knapping process, so knappers could vary the outcome by choosing to hold the piece in their hands, rest it on part of their body, or place it on a stone or wooden anvil.

The finishing elements of the design, such as notches and serrated edges, required the removal of tiny, regular flakes from the edges of the tool. This stage of tool making was critical, as a single ill-placed blow could destroy the entire piece. For this reason the final stage was undertaken using pressure rather than striking, with the knapper exerting a strong, constant pressure until a flake gave way as desired.

One form of knapping, known as monofacial reduction, created tools by working only one side of the workpiece. This technique required the knapper to strike the naturally flat face of the flake, aiming to remove chips from the other side. In profile, monofacial pieces are asymmetrical, with one flat face and one convex face. Bifacial reduction, in contrast, is a technique in which the knapper works on the entire surface of a piece on both sides, leaving a tool with no flat side. In profile view, both sides of bifacial pieces are convex.

Stone knapping has been used to make cutting, scraping, and perforating tools in the Americas since the earliest human times, and is still used by some indigenous groups.

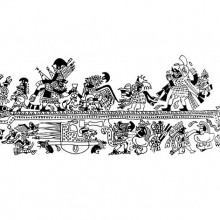

A few selected examples help show the quality of stoneworking among the ancient peoples of the Americas. Around 4000 BCE, fishermen on the north coast of present-day Chile worked huge and very thin bifacial blades up to 30cm (12 inches) long, from lustrous white, yellow, and red fine-grained silica. These tools, apparently used as knives, were greatly valued and were left as grave goods. Around the year 500 CE in Mesoamerica, workmen took advantage of the region’s high quality obsidian to create very thin and sharp pieces, with extremely fine cutting edges. The Aztecs of around 1400 CE created the so-called “eccentric flints”, blades crafted with great precision from flint or obsidian in shapes of spirals or waves, which were used as ceremonial sacrificial knives and were also buried as temple offerings. Images 3, 4, 5