Certain metals—known as native metals—can be found naturally in their pure form, but most metals are normally contained in rock as ore. Native metals are very malleable and can be worked by striking them with a hard object. This technique, called hammering or beating, is the oldest form of metalworking. The extraction of metal from its ore is a more complex procedure; first, the correct minerals must be identified and mined, often from below the ground. The ore is then purified using fire, often using crucibles and furnaces, allowing the metal to be smelted and separated from the rest of the rock. The use of smelted metal allowed items to be made using moulds, hammers, chisels, and files. This set of techniques and knowledge is known as metallurgy.

In addition to copper, iron, gold, and silver, human groups have made use of other metals such as lead, tin, and platinum to produce artifacts with different characteristics—color, finish, strength, and flexibility. The alloys most used in ancient times were based on copper, which was transformed into bronze through the addition of tin or arsenic. The result was a stronger, lighter-colored metal with a lower melting point and unique resonant properties, allowing it to be used for making such items as highly sonorous bells. Other important alloys include electrum, a mix of gold and silver that was used in Ancient Greece, and tumbaga, an alloy of gold and copper that was widely used in the northern Andean region in pre-Colombian times.

The earliest objects made from native copper were produced in the Middle East (Iran and Anatolia) around 9000 years ago. Metallurgy was developed approximately 6000 years ago in the area of Mesopotamia and the Balkans, and from there this technology spread rapidly throughout the Old World, with copper being the most widely used metal. The use of alloys increased around the year 3000 BCE, giving rise to the Bronze Age in Europe and Asia. Around the year 1000 BCE, iron replaced copper as the most common material used to make agricultural tools such as ploughs and weapons of war.

Metallurgy was discovered independently in the Americas, where the earliest finds of hammered gold and copper sheets date back to around 1500 BCE in the Central Andes (Andahuaylas and Cupisnique), while the first evidence of smelting appears around 1000 BCE in the mountains of Peru. To the South, around Lake Titicaca, the earliest evidence of smelting dates back around 3000 years and consists of slag, the waste rock that is separated from the molten metal. The metallurgy of the Central and Southern Andes (Peru, Bolivia, Northern Chile, and Argentina) was based mainly on copper and its alloys, which were used to make implements and tools (such as knives, axes, chisels, tweezers) as well as ceremonial items and personal adornments (including ear ornaments, rings, masks, and small bells). However, some objects were also made from silver and gold.

In northwestern South America, in the region between present day Ecuador and Costa Rica, a separate metallurgical tradition developed, the earliest evidence of which is found in copper artifacts dating back to around 500 BCE. By 400 CE this metalworking craft had become very sophisticated, with the use of tumbaga (a copper-gold alloy) and the manufacture of complex pieces using a casting technique known as the lost wax method. Around 1200 CE these groups began to work with platinum, a metal that is far stronger and more heat-resistant.

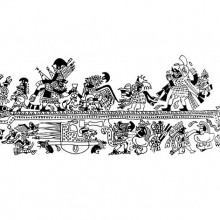

Metallurgy in Meso-America was a different story. The earliest evidence is found in western Mexico around the year 600 CE, influenced by the technology of northern South America, as there seems to have contact among cultures and even trade between the two regions along the Pacific coast. It is noteworthy that the people of the Mayan civilization, which built the great city of Teotihuacán, had no knowledge about the use of metals until this spread into the rest of the region around the year 1200 CE.

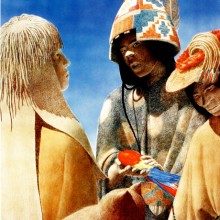

Metals were considered sacred materials by many cultures of the Americas, being associated with the gods owing to their remarkable luster and color. In both Meso-America and the Andean Region gold, yellow and untarnished by time, was identified with the Sun and other male deities, and was also linked to fertility and agriculture. Conversely, silver–pale in color and subject to corrosion–was identified with the Moon, with water and tides, and with goddesses, and thus also linked to fertility.