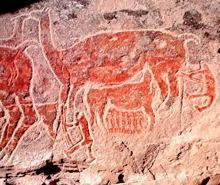

The Semi-arid North of Chile is a territory in which the Andes Mountains and the Coastal Mountains converge, virtually eliminating the Intermediate Depression, with rivers forming transversal valleys where semi-arid plant species such as chañar and algarrobo trees grow. The coastline here offers a rich and stable source of food throughout the year. The region’s first inhabitants arrived at the end of the Pleistocene when temperatures began to rise, the ice retreated, and the territory began a process of desertification that has continued to this day.

How to Arrive

El Museo se encuentra ubicado en pleno centro de Santiago, en la esquina de las calles Bandera y Compañía, a una cuadra de la Plaza de Armas.

Tickets

Chileans and resident foreigners: $1,000 Foreigners: $8,000 Chilean students and resident foreigners: $500 Foreign students: $4,000

Guided Visit

El Museo cuenta con un servicio de guías, sin costo adicional, para los establecimientos educacionales.

Information for Teachers

Invitamos especialmente a coordinarse con alguno de nuestros guías para programar una visita o actividades de motivación y seguimiento que aprovechen de la mejor forma la experiencia de visitarnos.

Audioguides

Download recordings of the Permanent Exhibition display texts in English, French, Portuguese and Spanish here. These audioguides are in mp3 format and are arranged by cultural area, following the same order as our exhibit galleries. Descargue desde esta página audioguías en castellano, inglés, francés y portugués con los textos de las vitrinas de la […]