Modern Aymara religion is a syncretic belief system, a mixture of custom—the group’s traditional cosmic vision—and religion—practices of the Catholic Church. Together, these two systems form a whole that is called ‘liturgy’. This syncreticism is particularly evident in community festivals celebrated on the feast days of patron saints, during Holy Week, and on All Saints’ Day.

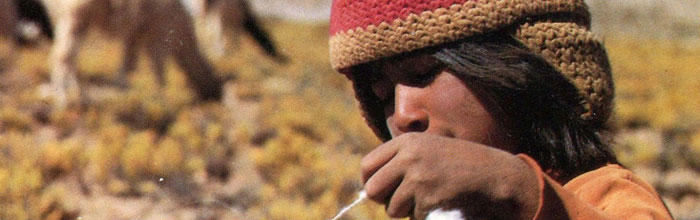

The group’s belief system follows the seasons of the year and is structured around key annual agricultural and natural events. The Aymara have a mythological, humanized and spiritual view of their environment, making it a key component in their world view and ideology, which seeks to define their place in nature and their responsibility towards it in everyday life.

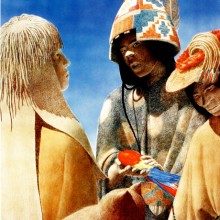

Their oldest belief systems are based on worshiping the spirits of the great mountains, the Achachilas, Mallkus and T’alla or “Providers”. These male and female spirits wield enormous power over peoples’ lives by controlling the climate. Other key Aymara figures include Pachamama, also known as the Virgin or Mother Earth, who brings forth all life (plants, animals and human beings); and Amaru, the serpent, which represents the courses of rivers and streams. These three spirits are linked to the origin, abundance and distribution of water, the giver of life, and to the natural ordering of the ecological and economic framework of the Aymara way of life. These three entities also determine the structure or hierarchy of the Aymara social order and political economy. For example, the social, political and spiritual capitals of the Aymara subgroups are all located in high-altitude pasture lands of the north-eastern region.

Every aspect of Pachamama is alive and has a name, a purpose and a destiny. Sacred locations may offer protection or danger, but all are to be respected– in some cases through worship and offerings. Some places are considered especially powerful; these include peaks, or Piru partes, and freshwater springs. Archaeological sites are also places worthy of respect, as they are the dwelling places of the ancestors, who are known as ‘the kind ones’ or ‘the grandparents’. The mythological triad mentioned above also has an ecological-ideological component, as the Aymara believe that individuals should always strive to achieve and maintain Tinku, an ever-changing balance in life.

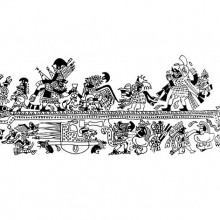

Aymara cosmology has undergone many changes as a result of dominance by the Inka and then the Spanish colonial powers. Over time, therefore, the triad of Mallku-Pachamama-Amaru was transformed into the Christianized Arajpacha-Akapacha-Manqhapacha, (Heaven-Earth-Hell), expressing the Aymara subordination to colonial and neo-colonial society.

In the Aymara vision, time runs in cycles that are defined by the seasons of the year, which in turn determine the dates of agricultural activities and religious ceremonies. These events are part of a larger cycle, known at the Pacha, which is constantly being renewed through a process of ‘revolution’ referred to as Kuti. This rhythmic, organic concept of time is interwoven with a more linear view of historic and mythological events: the beginning, which was the era of the sun, the time of the Spanish Conquest and colonialism, and the awareness of a future Kuti.

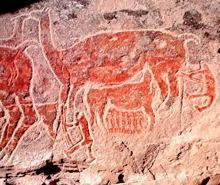

Traditionally, the Aymara have buried their dead in a variety of ways: in stone dolmens (with four walls and a roof); directly in the ground, both within and outside of houses; in cylindrical graves; and in small cairns. In the past they also built funeral monuments known as chullpa. These adobe towers were sometimes beautifully painted and were used to bury the ruling elite in pre-Inka times.