Chile under the Inka Empire – 2009

An architecture at the service of the empire

Chungara

The Tambo of Chungara

South of Chungara Lake, strategically hidden on a hillside, Tambo de Chungara consists of a row of seven rectangular rooms located in the upper part of the site. Its doors open onto a stone corridor and a large rectangular patio, both built upon a man-made terrace below the level of the rooms. At its southern end, there is a rectangular platform similar to an ushnu. The site is entered by going up six stone stairs and along a corridor between the platform and the patio. The best preserved walls are more than 2 meters high and were built with stones brought from neighboring volcanoes and worked at the site itself into massive blocks that are cut straight and tightly fitted. When the four rooms were in use, their wallswere elegantly plastered with fine mud, producing a hospitable environment that

protected travelers from the coldness of the high plateau nights.

It is believed that the Inka directed the raising of llama and alpaca herds from this place. Along with Tacora, Pisarata, and Ancara way stations, Chungara was one of a series of small settlements situated above 4,000 meters a.s.l. that controlled the State-owned herds grazing in the rich meadows of the Arica highlands. It has also been suggested that the place was used for loading and unloading of llamas used as beasts of burden. The quality of construction, however, indicates that its original purpose was more important. Taking into account the Spanish chroniclers’ stories that Topa Yupanqui and his army passed by Lake Chungara to put down an uprising of the Colla people at Lake Titicaca, it is possible that these ruins were actually the headquarters at which the Inka military commanders planned the attack that surprised the rebels from behind. Indeed, one can imagine the sovereign inspecting his troops from the platform at Tambo Chungara before leading them into battle.

The site may have been used later as a government cattle station or simply a caravan stop. In the early 20th Century it was occupied by an Aymara herdsman and his family.

Inkahuano

The Inkaguano taypi – a place that unites opposites.

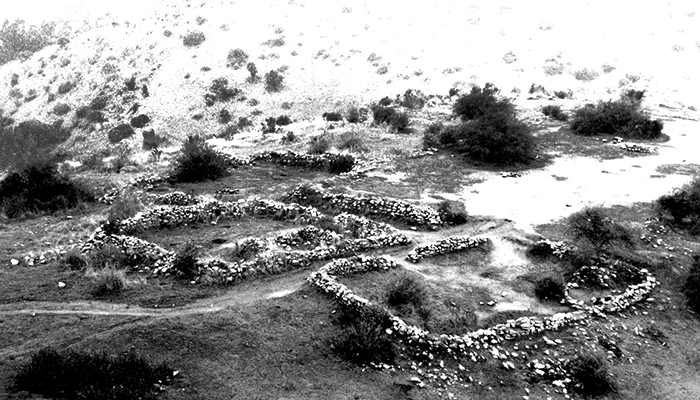

The Tambo of Inkaguano is one of the best preserved examples of Inka provincial architecture in Chile. It is located in the Tarapacá altiplano, close to the presentday town of Cariquima, beside an Inka transverse road that connected the Bolivian altiplano with the Tarapacá valley. It is an area of scrubland and grasses, with rock outcroppings and a number of freshwater springs, two recurrent symbolic elements in this kind of Inka installation. A number of sacred hills surround the area, including Sojalla, Queitani and, a little further off, Tata Jachura,the summit of which contains Inka structures.

Upon a platform carved out of the hillside and fortified by a retaining wall on the slope side, there is a rectangular square surrounded by a kallanka (administrative hall), four qolqas or rectangular storehouses placed in the form of a cross, and a kancha (main enclosure) of three residential units with their openings facing the central patio. The kallanka and the residences of the kancha still have the gables that supported their A-frame roofs. Adjoining this section are two large adjoining rectangular enclosures of indeterminate function. A canal in the upper part of the settlement collected rainwater that ran down the hillside and channeled it to a small ravine to prevent flooding of the buildings. The walls are a double row of stones partly worked, stuck together with mud mortar and covered over inside and out with a thin layer of fine mud plaster. A number of buildings have doorways in the typical trapezoidal form found in many Inka buildings. On the periphery of the site, a group of thirty circular and rectangular enclosures indicate that this installation was built on the site of a previous local settlement.

Situated in the center of a productive zone that came under secular dispute, during the Inka reign this small government outpost was staffed by officials who settled disputes among the people of the altiplano and those of the Tamarugal pampa. Close to the site, at the foot of mount Taypicoyo, a line of eight stone pillars or sayhuas may have been part of a boundary that came under dispute between the Tarapaca and Caranga chiefs in the 17th Century. When the Spanish authorities were asked to settle this dispute, note was made that the boundary “dated from the time of the Inka.” The Tambo of Inkaguano may therefore have operated as a taypi or territorial mediation center for the region’s main inhabited zones. Indeed, its function seems to have been more ceremonial than productive and its occupation much more sporadic than its imposing buildings would suggest. While its counterpart in the highlands must have been an important administrative center in the Oruro altiplano of Bolivia, its counterpart in the lowlands was certainly the town of Tarapacá Viejo, a large pre-Inka settlement that was partially remodeled during Inka times and occupied by the Spanish until the early 18th century. Today, the ruins of Tambo of Inkaguano are jealously guarded by the local Aymara inhabitants of the nearby hamlet of Quebe.

Turi

Ritual violence at Turi

With around 620 enclosures, Turi was the largest Atacameño town. It is located some 40 km east of Chiuchiu, in the Upper Salado River basin, the most important affluent of the Loa River. In pre-Inka times it stood at the center of a series of ravines that were densely populated and rich with grazing pastures, agricultural land and mineral resources. Situated on a dark lava plain, it overlooks a large pasture and controlled a hinterland that included the village of Likán in Toconce, the Caspana Valley, Cerro Verde copper mine, the village of Topaín and the agricultural settlement of Paniri, among other places.

When the Inka gained control of Turi, they destroyed the people’s most sacred sector and installed their emblematic structures in their place. They razed the sector where the local inhabitants had worshipped their ancestors, building an enclosure with three rooms. In the process at least three chullpa towers were torn down to the foundations, an act of ritual violence that was also practiced in other Andean towns such as Los Amarillos, in the Humahuaca ravine (Argentina), where the Inka destroyed the tombs of the three tutelary gods of that community.

At both sites, the practice suggests that the local population did not submit to the empire peacefully but apparently opposed the invaders. Later, in a radical rebuilding stage in Turi, the Inka built a very high wall and demolished the original enclosure, raising in its place a square and 12 enclosures, including two administrative halls (kallanka), one of which still stands in the square. Built on solid stone foundations and with adobe slab walls, the remaining hall is 26 meters long and is the largest in our country. Instead of foundations, in one of the corners they buried the skull of a 30 year old man, an offering that seems to have finally sealed the alliance with the native population. Ultimately, however, this foundation rite would destabilize that part of the building.It has been said that the Inka generally preferred to situate their administrative centers near but not within local settlements. In Turi they built the road that runs from the altiplano of Lípez to San Pedro de Atacama right through the town. However, the settlement did not operate as simply one more way station of the road system, but as one of the principal Inka administrative centers in Atacameño territory.

Viña del Cerro

Metal smelting at Viña del Cerro

In the Copiapó Valley, the site of Viña del Cerro was used as a stockpile for much of the country’s copper production. In the upper valley the alluvial fan formed by tributary rivers—the Jorquera, Pulido and Manflas—offers abundant pastures,streams, mining deposits and natural routes to all points on the compass. There the Inka built more than 30 settlements, including Iglesia Colorada, Pukara de Punta Brava, the administrative center of La Puerta and the Viña del Cerro facility,the only Inka metallurgy center known in Chile and one of the few registered in the Andean region.

On the summit of a hill at Viña del Cerro, a place formerly known as Painegue, the Inka built a settlement of four structures made of stone and adobe blocks that were used for different purposes. The kancha was a large walled rectangular enclosure with three openings onto the large patio, each with two rooms to house up to six corvée laborers (mitimaes). In one corner of this large space, up seven steps, is a platform or ushnu, from which the center was overseen. No doubt this was the location of the hospitality ceremonies that the Inka State held to recompense the conscripted workers for their work. Another struc ture, situated in a hollow, is a small walled enclosure with a room inside that is equipped with a poyo or Andean bed. This was apparently the quarters of the Inka official in charge of the facility. The third unit is a rectangular house situated beside a spring flowing out of the hillside, where the operator in charge of the water supply would have resided. The fourth structure, positioned on a hill exposed to strong winds, consists of the foundations of 26 huayras or furnaces, built in three rows. The walls of these would certainly have had openings for air circulation to ensure the high temperatures necessary for smelting ore would be reached. These smelting ovens, along with remains of ore, grinding implements, slag, pieces of ingot molds,crucibles and other specialized instruments show clearly that this was a metallurgical operation. However, the metal smelted left the place only partially finished, bound for the craft workshops on the other side of the Andes where it was melted down again to manufacture axes, knives and other objects in the Inka way.

It is estimated that the upper Copiapó metallurgical facility was permanently staffed by 18 to 20 male and/or female workers, most of them from nearby settlements such as Punta Brava, La Puerta and the area surrounding Viña del Cerro itself.

Los infieles

Los Infieles of Elqui

Along a tributary of the Elqui River, very close to the Pacific coast, Los Infieles is the largest Inka site found to date in the heart of Diaguita territory. Its fifty or so enclosures stand on a raised plateau, halfway up the mountain of the same name in an area rich in minerals and close to what was likely a crossroads of the Inka highway network. The settlement includes five main architectural units, most of which could be classified as kancha structures. They consist of large four cornered or externally attached enclosures. The site was used as a camp for the corvée laborers performing their mandatory service in the neighboring mining operations.

The camp’s food consisted of marine resources from the coast and inland resources from the nearby Elqui valley. Waste found at the site indicates that its occupants’ diet included rhodents, camelid, sea lions, fish and shellfish, but would also have included carbohydrates, as the agricultural mita (tribute) system would certainly have been imposed upon the native farming populations of the Elqui Valley. In the historical chronicle of 1558, Crónica y Relación Copiosa de los Reinos de Chile (Chronicle and Detailed History of the Kingdoms of Chile), Jerónimo de Vivar relates that when the inhabitants of this valley refused to open a community waterway, the Inka put 5,000 of them to death. The author also makes it known that as part of their punishment some of the surviving members were moved to other provinces of the empire.

Ojos de agua

Tambo Ojos de Agua

Sixty kilometers east of the present-day city of Los Andes, on the north bank of the Juncal River some 200 meters from a freshwater spring, Tambo Ojos de Agua represents the last stop on the Inka Road before it begins the ascent through the mountains to Mendoza. For those coming from the other side of the Andes, in contrast, it was the first place where animals could be pastured and the weather bearable after the harsh mountain crossing.

The site is situated on a broad plain at the base of a group of hills that protect it from the winds blowing up the valley from the Juncal Canyon. It consists of an open-ended U-shaped outside wall that runs from the river side along the southern hill and then turns north along the foot of the western hill, until reaching a large rock, where it turns for a short stretch towards the east. Beyond the rock,two walls –one straight and one L-shaped—flank a 150- meter long section of Inka road coming from Argentina through the Uspallata pass. A straight wall, perpendicular to the last two but divided by the modern Santiago-to-Mendoza highway, also seems to be part of this complex. The settlement has 24 rectangular enclosures, most inside the perimeter wall, with a few outside of it—three of these at least are beside the Inka road. Two circular structures that are considered to be storehouses (qolqas) can also be seen on one of the surrounding hills. Excavations of the site found sherds of undecorated pots and pitchers, as well as decorated aríbalo jugs, dishes and aisana bottles, bowls in the Diaguita style, Inka-Paya (Argentina) pieces and bowls reminiscent of the Aconcagua style.

Other remains include projectile points, copper needles, slate disks and freshwater and marine mollusk shell beads. Judging by the content of the middens, the occupants of this place ate mainly llama and guanaco meat, mackerel and hake fish, maize, chili peppers, beans, quinoa and potatoes. The most obvious function of this site was as a way station for the mountain crossing, and therefore it must have ell staffed with corvée laborers. However, it has also been suggested that it could have been one of the main stops on the pilgrimage to Mount Aconcagua, the summit of which housed one of the region’s most important wakas or Inka sacred places. In colonial times and into the 19th century, this way station was intensely occupied by travelers crossing the Andes, including one of the six columns of the Liberating Army, which passed by the place in 1817. Today, car travelers journeying easily and comfortably along the international highway rarely suspect that they are passing by one of the most crucial and long-awaited stops on the historic journey across the Andes.

Chena

Chena Fort

The Inka fortifications located south of the Maipo River display a certain degree of instability and the need for defense against hostile groups from the south. To address this issue, we examine the sites of Pukara de Chena and Cerro Grande de La Compañía.

For the Inka, war was closely related to religion, with both the combatants and their adversaries endowed with intense ceremonial symbolism. Consider the case of Pukara de Chena, south of Santiago. This Inka site was built upon a spur of the Chena range, visually dominating the middle reaches of the Maipo River, the narrow passage at Paine and the sacred Inka shrine of Chada, which controlled a settlement of the Aconcagua culture located at the foot of this isolated hillside.

Chena is a strategic location for overseeing the movement of people along a rugged spur and the features of its construction leave little doubt that it was a fort. It has two concentric defensive walls, now in ruins, that circle around most of the settlement. On the south side of each there are entryways that are controlled from two watch towers. The upper wall encloses a large part of the hill, on the summit of which there is a flat area or citadel with a large rectangular walled zone with a number of smaller structures attached to it on the outside: one on the north wall, another close to the northwest corner and three adjoining the south wall, two of which leave a corridor as the only access point to the summit esplanade.

The cemeteries associated with the settlement indicate that their occupants were not all temporary residents, serving as conscripted soldiers who returned to their places of origin after serving their term, but residents with a long enough history in the area to be buried at the site. In fact, there are more Inka local ceramics found as grave goods than any other style, with Diaguita-Inka pieces notably absent, indicating that those buried there were usually Inka subjects from Central Chile. As in many Andean forts, in the fort at Chena the Inka and their

allies would have fought against their enemies protected not only by defensive walls but also by the power of their ancestors.

The Company

The bastion of Cerro del Inga

South of the narrow passage of Paine, on the mountain Cerro Grande de La Compañía, also known as Cerro del Inga, stands the southernmost Inka settlement of all of Tawantinsuyu. It is a fortified site that overlooks an extensive part of the region. The site consists of three concentric walls that protect the promontory at different levels, and 19 structures, including five four-cornered residential enclosures, a terraced structure, another large covered circular structure and 11 smaller circular storehouses. The innermost part of the settlement stands on the summit of this inselberg. Like Chena Fort, entry to the citadel at the top is through a narrow corridor between two buildings that controlled access to it.

The fort shows that the Inka had to deal with threats from hostile groups from the south. For instance, European chroniclers were told that Topa Yupanqui decided to establish the southernmost boundary of Inka territory at the Maule River. Perhaps this was a diplomatic way of saying that the Inka army encountered here the same tribes that would later offer so much resistance to the Spanish conquerors in the Arauco War. The Inka defeat in the Battle of Maule, which is mentioned by several chroniclers, probably put an end to the Cuzco Empire’s eagerness to conquer southern Chile once and for all. For this reason, no clearly Inka settlements have been found further south than the fort at La Compañía.

The La Muralla site, situated south of the Cachapoal River facing the Tagua Tagua lagoon, has walls with foreign characteristics but has not been identified as Inka. Thus, in this place 2,500 kilometers from Cuzco, La Compañía marks the southernmost boundary of effective Inka rule known to date; beyond this point there lay an extensive, unstable frontier zone plagued by warrior tribes, into which the Inka only made occasional incursions.

Of course, this situation did not prevent the Inka from establishing contact and entering into a variety of agreements with these groups. Proof of this is found in the Inka ceramics and metal axes that have been found as far south as Valdivia, where they probably arrived after changing hands more than once. Also, some local cemeteries, such as that found in Rengo, show evidence of contact with the Inka. More proof that the frontier was unstable at this point is found at Tren Tren, a hilltop site located 22 kilometers southwest of Cerro Grande de La Compañía, whose name carried a strong strong symbolic connotation in the Mapuche belief system. The site contains a tomb located inside a sealed cave, where the partial cadavers of four children aged nine months to nine years old were found. The ceramic vessels accompanying the children as grave goods display mainly local ceramic styles; interestingly, though, the grave also contains a number of Inka ceramic vessels similar to those found throughout Tawantinsuyu. Although it is not possible to undertake an in-depth analysis of this frontier symbolism, it is notable that in the Araucanía region hills with similar names functioned as landmarks, while in the north of the country certain hills were used as boundary markers between different ethnic groups and as meeting places where local chiefs gathered to resolve disputes and make agreements.