The Art of Copper in the Andean World – 2004

- From stone to jewel

- Metal tools

- Chromatic palette of copper

- Metallic sounds and glitters

- Bronze bells

- Metals for taking away life

- Copper on the shaman’s altar

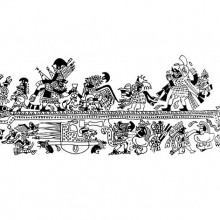

- Copper in the andean iconography

- Metallic bodies

- The face of death

- Food for men

- Food for the gods

- The power of the cailles

- Epilogue

- Galería de fotos

Bronze bells

The large bronze bells look like the small wooden cancahua with several clappers that were used in the Atacama desert for centuries. Hung from the neck of the leading llama it’s wooden sounds signaled the passing of the droves and the ritual caravans. The transformation of the cancahua into a bronze instrument meant that it became part of a more privileged and select environment. It grew in size and weight, becoming a powerfully sacred object because of its gleaming golden body and the potent metallic voice associated with its movement.

The wear marks of wear on these bells reveal their heavy use with multiple metallic clappers. A flange on the inner edge of these instruments absorbs this wear without deteriorating the sound. Slight movement makes the clappers produce a variety of rhythmic patterns. Only a pair of inverted human heads on the lower edge adorn the smooth outer surface. They have been interpreted as decapitated heads, hung as trophies, alluding perhaps to the human sacrificial rituals related to the propitiatory ceremonies for agricultural fertility. They also are often decorated with snakes and suris, or, Andean ostriches.

These tin-bearing bronze bells are among the pre-Columbian world’s biggest metal objects. Technically they represent one of the highlights of the metallurgical process in the Andes. Their large convex and burnished surfaces reflected the sunlight with an intense and golden shine, and their potent metallic sound stood out over all other known sounds. They probably symbolized the color, rays and, maybe, the “sound” of the sun.