The Art of Copper in the Andean World – 2004

- From stone to jewel

- Metal tools

- Chromatic palette of copper

- Metallic sounds and glitters

- Bronze bells

- Metals for taking away life

- Copper on the shaman’s altar

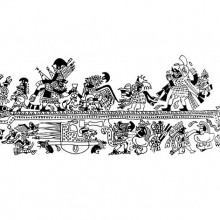

- Copper in the andean iconography

- Metallic bodies

- The face of death

- Food for men

- Food for the gods

- The power of the cailles

- Epilogue

- Galería de fotos

The face of death

The use of masks to substitute the face and to give an individual the qualities they represent, is a very common practice in different cultures around the world. In the pre-Columbian Andes masks were common, although very few were meant to be used in life. Most are associated with burial rituals. The metal pieces performed a central role in these rites, with gold and more often copper masks for the deceased elite in cultures like the Moche, Wari, Nasca or Sicán. These objects, together with burial offerings of rich clothing, fine ceramic vessels and jewels, among other things, glorified the life of society’s elite and communicated their high social position.

In the Moche culture, masks were placed directly on the face of the deceased while in Sicán they were put on top of a big textile bundle wrapped around the body. The aim was to replace the face of the dead person – that would inevitably suffer the ravages of decomposition – with a metal face whose shape, color, shine, durability and fixtures represented its most sacred attributes. With this powerful symbolic procedure, the dead from the governing elite reaffirmed the ties of their lineage with the deities, ritually transferring their political, social and economic rights to their descendents.