The Art of Copper in the Andean World – 2004

- From stone to jewel

- Metal tools

- Chromatic palette of copper

- Metallic sounds and glitters

- Bronze bells

- Metals for taking away life

- Copper on the shaman’s altar

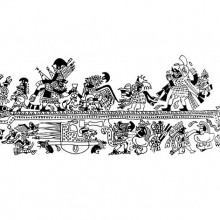

- Copper in the andean iconography

- Metallic bodies

- The face of death

- Food for men

- Food for the gods

- The power of the cailles

- Epilogue

- Galería de fotos

From stone to jewel

The Andean region has a wide variety and wealth of metal-bearing mineral deposits. But its irregular distribution prevented the pre-Hispanic populations from having access to these minerals, motivating the development of different extraction, smelting and metal alloy production techniques.

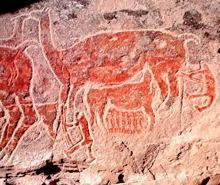

Pre-Hispanic miners followed the copper, gold and silver veins, opening up deep pits with wooden bars and stone shovels. The raw material was transported in leather sacks and baskets to the outskirts of their camps to be crushed and to separate the ore, or, useful mineral from the sterile gangue. The material was ground with heavy lithic hammers on stone paving or with the maray, or, “batan”, that consisted of a large concave bottomed boulder rocked with wooden levers over a flat stone. The selected mineral was moved to furnaces for smelting.

Miners also used to separate the most colorful copper and turquoise oxides, for making like necklace beads and other ornaments. The first step of cleaning and preparing the matrices from the mineral nodules was probably done at the mine itself, using percussion on stone anvils. Then, they shaped them by pressure with stone or bone awls. The beads were placed on wooden tablets with drilled holes where they were perforated with small quartz instruments. Finally, they were polished.

Instruments, as well as the raw materials of this small but important pre-Hispanic industry, are often found in the mines, like Las Turquesas Mine in El Salvador, or as part of the burial offerings of an ancient lapidary artisan in San Pedro de Atacama, both sites located in today’s Northern Chile.

Smelting in the wind

The most well known pre-Hispanic smelting artifact was the wind furnace, or, huayra. It was placed in open, especially windy places, to raise the temperature and smelt the mineral. The simplest model was a mound of stones with clay and ash mortar. This small tower acted like a chimney, with holes where the air entered naturally. Other times the air was blown in using long cane tubes. The crucible that collected the smelted mineral was on the bottom and the slag drained out one side of the huayra. Another kind of furnace was a portable ceramic one, although this model could have been an innovation introduced after the Hispanic conquest. It was a thick- walled, wide-mouthed vessel with holes on the bottom, where the live coals were placed and where the air was blown in through cane or ceramic blowers or nozzles. Small underground furnaces have been found that are plastered with clay and have openings for placing the live coals and for reviving the fire with the aid of blowers. Among the most commonly used smelting fuels was charcoal, made from algarrobo and chañar, resinous bushes like the Andean yareta and llama manure, or, taquia, which is highly caloric.

The crucibles were usually made of heat-resistant pottery that could withstand temperatures higher than 1000°C as well as the chemical action of the hot metal. Some of them had notches along their edges, for pouring or so they could be handled with wooden wheelbarrows. Other crucible models had a hole on the bottom, covered with a valve or “spigot”, to regulate the flow of liquid metal that was poured into the molds. Small ingots were made from the molds, which were used to make different objects by hammering them into sheets or by annealing to return the metal to its ductile state. They also manufactured pieces that were cast from liquid metal in molds, using the “lost wax” technique, whereby three dimensional sculptured objects or pieces with complex decorative elements were produced.