Quipu: Counting with knots in the Inka Empire – 2003

- Record-keeping with knots

- The quipu and writing

- Tawantinsuyu , the Inka Empire

- The Quipu, and the needs of an empire

- Quipus and tribute

- Basic parts of a Quipu

- Making a Quipu

- Quipus and numerical values

- Narrative Quipus?

- Los distintos usos del Quipu

- Quipu of Arica

- Quipucamayoc , Lord of the Knots

- Quipus in the colonial era

- Epilogue

- To know more about Quipus

- Crédits and acknowledgements

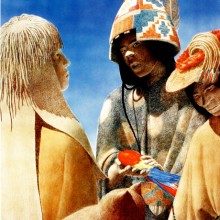

Quipucamayoc , Lord of the Knots

The quipucamayocs were the Inka State administrative officials specialized in the use of the quipu. The sons and grandsons of nobles or personages were trained in this occupation by the amautas, or sages, from a very early age. The most important quipucamayocs were the Secretary to the Inka and the Secretary to the Royal Council, followed by the Senior Record-Keeper and Treasurer of Tawantinsuyu, and the Administrator of Provinces. However, each city, village, and town – no matter how modest – had “scribes,” record-keepers and treasurers of the Empire.

The quipucamayocs assisted the administrators of the collcas, or state warehouses, in keeping track of the stored products inventory. They also helped the surveyors distribute land, the tax collectors manage their taxpayer information, and the astrologers predict the proper time to plant and harvest crops. They recorded births, marriages and the plots of land granted to newly constituted families. They registered on their quipus the amount of wool the llama herders obtained annually from the state flocks, and the quantity of corn the peasants harvested during the year, the coca leaves they gathered in the warm, humid valleys, and the potatoes, beans, cotton and quinoa they harvested on their land. The quipucamayocs knew each day’s calendar date, the distance they had covered since leaving any given town, how many articles of clothing had been woven, the number of vessels manufactured, the quantity of bronze axes that had been smelted, the amount of gold or copper mined, fish captured, or fertilizer that had been obtained from the guano islands. Nothing was overlooked by these skilled state record-keepers.

According to the Andean indigenous chronicler Guamán Poma de Ayala, through the strings and knots of the quipucamayocs, “the Inka governed the entire Empire.”