The art of being Diaguita

- A little history

- Chino Dances

- Ways of “being Diaguita before the Inka period

- The origins of Diaguita art and culture can be found in Las Ánimas

- Several ceramic styles coexisted in the Norte Chico, representing different modes of “being Diaguita”. One of these was the Fourth Style.

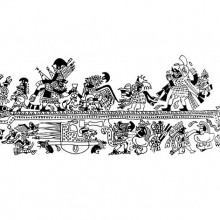

- Like many pre-Hispanic peoples, the Diaguita felt a need to represent themselves in their ceramics

- Color was not the only way in which the Diaguita expressed their identity

- Diaguita ceramics exhibiting bird, feline and reptile faces

- Diaguita tricolor vessels and their shamanic geometries

- Identities in transformation

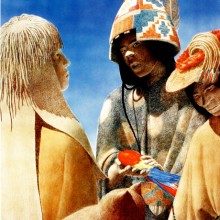

- The textiles of the Angualasto culture give us an idea of how their Chilean contemporaries, the Diaguita, dressed.

- Objects found in graves prove that Diaguita identity transcended death

- The Diaguita also had fertility cults

- Sounds and melodies accompanied Diaguita ceremonies and rituals

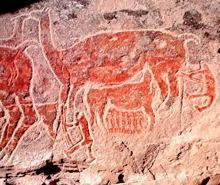

- Shamanic trance played a central role in “being Diaguita”

- By consuming hallucinogenic substances, certain individuals acquired the identity and powers of their guardian animals

- Ways of “being Diaguita” in Inka times

- After the Inka conquest, the Diaguita modified some elements of their culture

- The Diaguita served as agents of the Empire during the Inka expansion into Chile’s Central Valley

- As allies of the Inkas, the Diaguita helped with the administration of the Copiapó Valley

- The Diaguita and the “red metal”

- The Diaguita’s emblematic stone fascinated the Inkas

- The Norte Chico today: Diaguita, in their own way

- Epilogue

- Créditos

After the Inka conquest, the Diaguita modified some elements of their culture

Duck-shaped pitchers became more rigid in form, their spouts became narrower, and the color white came to dominate the decorative field. The figures represented on these pitchers no longer wear the characteristic headband, and the wide array of geometric designs formerly found on the bodies of ceramic vessels have been replaced by checkerboard and crosshatched diamond motifs. Additionally, the faces appear more severe, but the eyes are still painted with dark spots as though this specific feature, which evokes the kestrel, identified the figures with the wamán, the powerful royal falcon of the Inkas.